Hashiguchi Goyō – The Painter

The second issue of a three-part series on the life and work of Hashiguchi Goyō, a Japanese painter, printmaker, and book designer active in the early 20th century.

In last week's issue we looked at the early life of Hashiguchi Goyō and his career as an illustrator and book designer.

Parallel to designing books, Goyō continued to create oil paintings, many of which are based on studies from his days at art school.

He developed an approach combining the realistic expression of Western-style paintings, the flatness of Art Nouveau, and the stylized renderings of Japanese painting — showing influences from the compositions and moods of the Pre-Raphaelites and a fascination with ancient mythology.

Some of these paintings were publicly exhibited. For example Kujaku to indo on'na (Peacock and Indian Woman) at the Tōkyō Kangyō Kakurankai (Tokyo Industrial Exhibition) in 1907, and Hagoromo (Feather Mantle) at the first Bunten exhibition held in the same year. However, he gradually gave up oils after his works repeatedly failed to be accepted by Bunten’s admission jury in subsequent years.

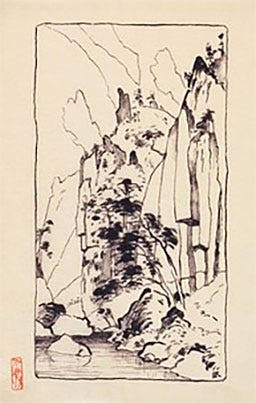

In addition to losing self-confidence in oil painting, he suffered from health issues that would plague him for the rest of his life. In the summer of 1910, Goyō traveled to Beppu in Oita Prefecture — a region famous for its spas and located on the same island of his birth — to recover. His visits to the hot springs and the beautiful landscapes inspired his creative direction in the following years. Sketches from this trip eventually formed the basis for his later woodblock prints.

But before he ventured into printmaking, he made a "last attempt" at oil painting in 1911, which proved to be a great success.

In February of that year, Goyō entered a Western-style oil painting, Kono Bijin (This Beauty), for an advertising competition sponsored by Mitsukoshi Kimono Store. It won first prize out of 300 submissions. The prize money of 1,000 yen, an unprecedented amount at the time, attracted much public attention. Goyō’s painting was reproduced as a lithograph poster and hung at over 500 train stations across Japan. In the advertising industry, this event marked a turning point from the era of illustrated leaflets to using posters as a popular medium to promote products.

Aligned with Mitsukoshi’s clientele, “the modern woman,” the poster’s aesthetic — as well as its subject, who wore her hair in the then-fashionable "203 Kōchi" style — reflects the trends of the time. Like in his earlier paintings, Goyō naturally combines realistic depictions and stylized elements. The composition draws on the classic Bijin-ga theme, or “pictures of beautiful women,” prevalent in Nihon-ga paintings and Ukiyo-e prints. Notably, the subject holds a picture book of woodblock prints, which hints at one of Goyō’s great passions.

The poster was printed using state-of-the-art lithographic printing techniques. Lithography was imported to Japan from Europe, where it had revolutionized the production of advertising posters in the 1880s. Essentially, the process involves making printing plates out of limestone and using them with oily inks that adhere only to the image painted on their surface.

Because the limestone undergoes virtually no wear during printing, a single plate can produce an almost unlimited number of copies. This allows for long runs without sacrificing quality, and the high unit cost decreases as the quantity increases — making it an efficient method for high-volume printing projects.

Hashiguchi Goyō’s work was reproduced by artists at Mima Printing Company in Ginza, who divided the image into more than 30 color plates. Lavishly printed to highest quality standards, the poster reflects Mitsukoshi's high-end sensibility.

To this day, the Mitsukoshi department store is synonymous with luxury shopping in Japan. The history of Mitsukoshi began in 1673, when Takatoshi Mitsui, a kimono fabric merchant, founded Echigoya Dry Good Store in Edo, present-day Tokyo.

Over the centuries, it catered equally to the Imperial Household, the nobility, and the ordinary middle and working classes. The store's goods were affordable and of good quality, contributing greatly to its positive reputation, which spread far beyond Tokyo.

In the aftermath of the Meiji Restoration, the store eventually broke out of the mold of the traditional Japanese retail format to adapt to evolving customer needs. In 1904, Echigoya was renamed Mitsukoshi and transformed into Japan's first Western-style department store. In 1914, Mitsukoshi cemented its image of being a modern, trend-setting retailer by rebuilding its store with Western-style architecture, echoing the Victorian buildings of 18th-century Europe.

Mitsukoshi had its finger on the pulse of time, evolving over the years. Still, it remained true to its origins, offering high-quality kimonos to fashion-conscious women.

A turning point in Goyō’s artistic direction

Goyō had been trying to shift away from oils for some time, searching for a new medium to spark his creativity. Invigorated by the poster’s positive reception and perhaps liberated by the prize money, he turned his attention to woodblock printing.

Next issue:

In next week's issue, we'll look at Hashiguchi Goyo's woodblock prints.

Previous issue:

Stefan Yanku adapted this Substack issue from two articles he published on The Arts of Japan’s website. For further credits and references, please visit the original article at https://artsofjapan.com/en/profiles/hashiguchi-goyo and https://artsofjapan.com/en/works/goyo-kono-bijin

I would like to thank Darrel C. Karl for kindly providing a photograph of the Mitsukoshi poster from his collection; photograph courtesy of the Japanese Art Society of America; photographer Alex Jamison.

The thumbnails of all other images are from the Kagoshima Digital Museum http://kagoshima.digital-museum.jp (fair use).

For copyrights and usage permissions, please refer to the statement on our website, available at https://artsofjapan.com/en/impressum.