Hyakutake Kaneyuki – The Painter

The second issue of a two-part series on the life and work of Hyakutake Kaneyuki, both a pioneering Japanese diplomat and painter active in the late 19th century.

Recap: In the first issue, we looked at Hyakutake Kaneyuki's upbringing and early career as a diplomat. We followed him and his superior, Nabeshima Nahohiro, on his first trip to Europe as a member of the diplomatic entourage of the Iwakura Mission. After arriving in London, the heart of the British Empire, in 1872, he enrolled at Oxford University to study economics. Beginning in 1875, at the age of 33, Hyakutake took weekly painting lessons from Thomas Miles Richardson Jr. – it marked the beginning of his path to mastering Western style painting.

Paris, Rome, and a masterpiece

In 1878, after concluding his studies at Oxford and staying in England for almost six years, Nabeshima and his wife Taneko began preparations to return to Japan to assume a post at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nabeshima may have realized that art was a valuable medium for understanding Western culture. So, remarkably, he encouraged Hyakutake to stay in Europe and further hone his painting skills. Thanks to Nabeshima's arrangement, Hyakutake moved to Paris, where he was able to devote a year to art alone. There, he studied oil painting with Léon Bonnat, a participant in the Salon in Paris and a professor at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

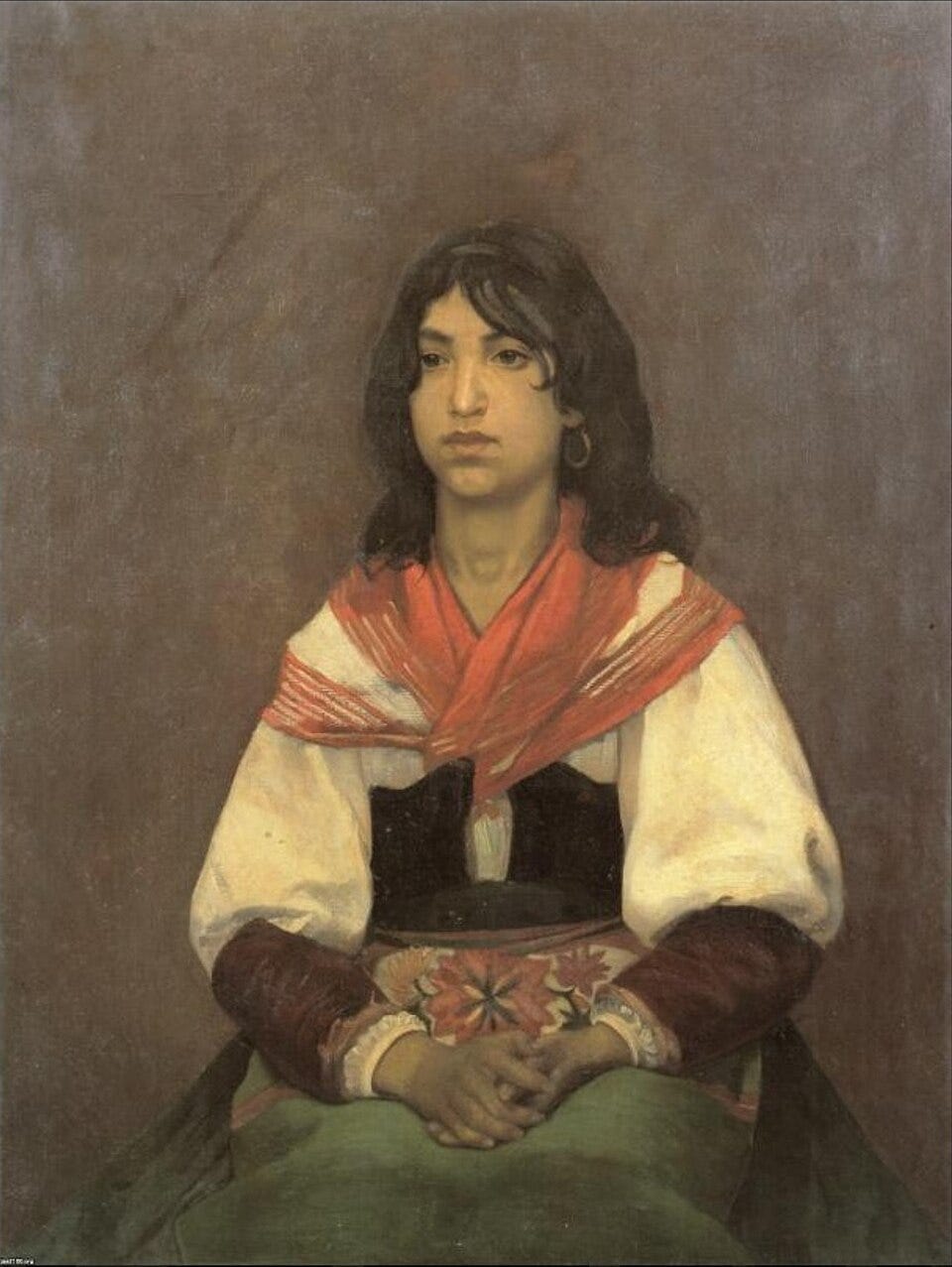

Hyakutake created some of his best and most representative works there, including Mandorin o motsu shōjo (Girl with Mandolin, 1879).

A year later, Hyakutake was recalled from Paris to Japan to receive his next government assignment. Now a career diplomat, Hyakutake was posted to Rome as First Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Italy, from 1880 to 1882. Again, he was working alongside Nabeshima, who was the ambassador. While serving as a diplomat, he studied under the painter Cesare Maccari, an honorary professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti of Rome. This was made possible through an introduction of Bonnat, Hyakutake’s teacher in Rome.

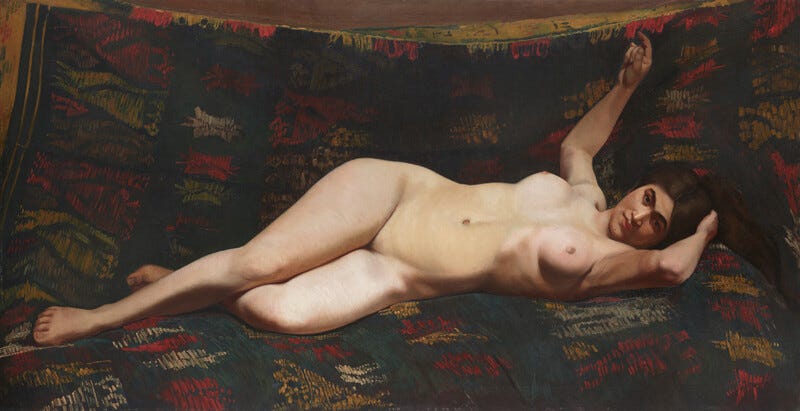

In Rome, Hyakutake completed his masterpiece: Ga-rafu (Reclining Nude), a true-to-nature portrayal of a reclining woman with a beautiful, intense presence. Dated 1881, it is one of the earliest oil paintings of a nude by a Japanese artist.

The Reclining Nude is depicted against a background of deep green tapestry with red, white, and yellow ornaments. The woman rests her head on her left hand, while raising her right arm, balancing her relaxed posture with a sense of movement. Fixing her eyes on us, Hyakutake achieves a beautiful portrayal of a woman with a captivating, powerful presence.

The whereabouts of Hyakutake's Reclining Nude were unknown for a long time. Hyakutake sent the piece from Rome to the wealthy Yatomi family in Saga, with whom he had a friendly relationship. Since then, it has never been displayed publicly. The painting reappeared at the 29th Saga Art Exhibition in 1948, 64 years after Hyakutake's death, thrilling the art world. The sponsoring Saga Art Association wrote in its journal, “It is a pleasure to exhibit this gem, which has never been shown to the public before.” Reclining Nude was later sold and is now in the collection of the Artizon Museum of the Ishibashi Foundation.

Another notable work Hyakutake created during his time in Italy was a portrait of Nabeshima, the Minister Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Italy, posing in full court dress. It was painted in 1880 by Hyakutake, while he we was working as First Secretary of the Japanese Legation in Italy.

The large format oil paining was prominently displayed at Japan’s embassy in Rome. The engravings on its golden frame seem to underscore Nabeshima's efforts toward harmonizing diplomatic relations between Italy and Japan. In the upper half, the frame is engraved with the Nabeshima family crest, while the bottom corners show the Italian peninsula and the Japanese archipelago.

Portrait of Nabeshima Naohiro appears to have a clear purpose: to portray a dignified government official of a respectful country on par with Western powers. Therefore, it was likely important that the painting was made by a Japanese artist, to symbolize that Japan had mastered Western technology by adopting its oil painting techniques. A painting with such gravitas would be a serious commission for any artist.

As mentioned in the previous newsletter, Hyakutake had taken up oil painting in 1875 while he was in London. Even though he had developed an earnest passion for the art, he could still be considered a novice. Nabeshima’s choice to have Hyakutake paint him can be seen as a testament to the mutual trust and respect they held for each other. When Hyakutake painted Nabeshima, they had known each other for about thirty years. Their shared journey began as boys studying together before evolving into a professional relationship as adults. When Nabeshima ascended to the position of daimyō, Hyakutake served as his assistant, and he remained by his side throughout his life. After the Meiji Restoration, they traveled together to the United States as part of the Iwakura Mission and subsequently spent six years in England. Eventually, they were posted to Rome in 1880 to establish relations between Japan and Italy.

Given their long and close association, this painting perhaps also offers an intimate glimpse into how Hyakutake perceived Nabeshima, capturing the person beyond superficial appearances.

Coming home with a legacy

Returning to Japan in 1882, Hyakutake became deputy director of the Trade and Industry Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Trade. Unfortunately, he soon had to retire to his hometown in Saga, suffering from tuberculosis, and died in 1884 at the age of 42. He is thought to have left only a small number of works, about 40 pieces, mostly painted during his time in Europe.

Although Hyakutake was primarily a government official, his works are among the finest Western-style paintings of the early Meiji period due to the academic techniques he learned firsthand in Europe.

Remarkable as he was, Hyakutake had little direct influence on the development of Western art in Japan. For one, his prolonged absence in Europe limited his interactions with the Japanese art community. Furthermore, most of his works were painted during his time in Europe, and some of his finest creations, such as the Reclining Nude, were gifted to private individuals and remained unseen by the public for decades.

Due to unfortunate timing, there was no formal art institution to pass on his knowledge to a broader group of students after he came back from Europe. The Technical Arts School — the only academy in Japan that taught Western art — was established in his absence in 1876. It closed its doors within a year of his return, partly due to the rise of traditionalist sentiment that rejected the radical Westernization of Japanese culture.

Coinciding Hyakutake's death in the mid-1880s, Japanese painters like Kuroda Seiki traveled to Europe to study Western painting. Eventually, a new academy teaching Western art opened its doors in 1887. But by then, the European painting world was changing with the rise of Plein Air and Impressionism. Japanese artists followed these trends, and as a result, the academic techniques Hyakutake had learned lost their appeal. And so Hyakutake's work was forgotten.

Still, Hyakutake’s study of the techniques and spirit of European academicism inspired at least some Japanese artists to paint in the Western style. One of his few students, Shōdai Tameshige, also from Saga, became an active figure in the Western-style painting scene and was involved in the founding of the Western painting group Hakuba-kai, together with Kuroda Seiki and others.

Okada Saburōsuke, another Western-style painter from Saga, said that he was greatly influenced by Hyakutake’s work from an early age. He developed a strong interest in painting after seeing Hyakutake’s paintings at Nabeshima’s house at a young age, and even as a child painted pictures with shadows.

In his short life, Hyakutake Kaneyuki became a pioneer in both the art and diplomacy of 19th-century Japan precisely because he bridged those two disparate worlds. As a champion of embracing the best of Western culture, he helped the fledgling Meiji government establish diplomatic relations in Europe. And as an artist with eyes open to the unfamiliar, he led the way in bringing Western-style painting to Japan.

Thank your for reading The Arts of Japan’s Substack newsletter.

I hope you enjoyed it! If you did, please take a moment to hit the heart button at the top of the email or in the Substack app.

Feel free to leave a comment! I would love to hear your thoughts. If you have additional information on the subject or found an error, your constructive feedback is always welcome too.

And, of course, feel free to share the post or subscribe to The Arts of Japan if you haven’t yet done so:

Stefan Yanku adapted this Substack issue from an articles he published on The Arts of Japan’s website. For further credits and references, please visit the original articles at https://artsofjapan.com/en/profiles/hyakutake-kaneyuki,

https://artsofjapan.com/en/works/hyakutake-ga-rafu and https://artsofjapan.com/en/works/hyakutake-nabeshima-naohiro-zo

For copyrights and usage permissions, please refer to the statement on our website, available at https://artsofjapan.com/en/impressum.