Mizuno Toshikata – Part 1: His rocky path to becoming an artist

The first part of an eight-part series on the life and work of Mizuno Toshikata, an ukiyo-e artist and nihon-ga painter active during the turbulent Meiji period.

Introduction

Mizuno Toshikata was a versatile artist who bridged Japan’s artistic traditions across the tumultuous Meiji period. Best known for his bijin-ga prints depicting elegant ladies in historical and contemporary settings, his diverse work also included kuchi-e illustrations, musha-e warrior prints, and senso-e war prints. While Mizuno Toshikata enjoyed commercial success creating woodblock prints, he also cultivated his passion for historical paintings and participated in academic art groups. Through his involvement in these circles and as a teacher of outstanding artists, Toshikata had an active voice in the development of modern Japanese art.

I am deeply fascinated by his work, which reveals qualities on many levels. From the mastery of his artistic craft to the emotional range he expresses in his work. He can capture the violent intensity of a fierce warrior as well as the tenderness of a young daydreamer. Interestingly, he composes his works with a remarkable economy, concentrating on the essentials while paying attention to detail. It feels like a contradiction, but I believe that his attention to the small things informs his ability to capture a scene or a person’s pose with as few elements as possible. I imagine this comes from a careful observation of the people and objects that populate his paintings. And indeed, as we will see later, he was one who formed study groups with other artists and experts to meticulously research the topics that featured in his work. In addition, he seemed to be attuned to the rapidly changing society around him, and digested it in his work.

One of Toshikata’s great students, Ikeda Shōen, recalls that her sensei instructed her to “paint the female figures in her paintings not just as pretty dolls, but as living people, as if they would bleed if you cut them. It is important to capture the elegance and spirit of the people you paint.” When I look at Toshikata's work, I have the feeling that Toshikata lives by this mindset, which breathes life into his remarkable creations.

In this eight-part newsletter series on the life and work of Mizuno Toshikata, I would like to follow his artistic journey in the following steps:

His rocky path to becoming an artist

Finding his niche

Art from the frontlines

The literary frontispiece

An eye for beauty

A passion for history

The new Japanese painting

A living legacy

In this first part, I would like to look at his childhood and the harsh headwinds he faced on his path to becoming an artist. His resilience and grit is deeply inspiring.

I hope you enjoy reading as much as I enjoyed writing about Toshikata!

Early life

Kumejiro Nonaka, later known as the artist Mizuno Toshikata, was the son of a master plasterer. His mother left them soon after his birth, and he was raised by his father and stepmother. Born in 1866 just two years before the Meiji Restoration, Toshikata was part of the first generation of children to enjoy (compulsory) public schooling.

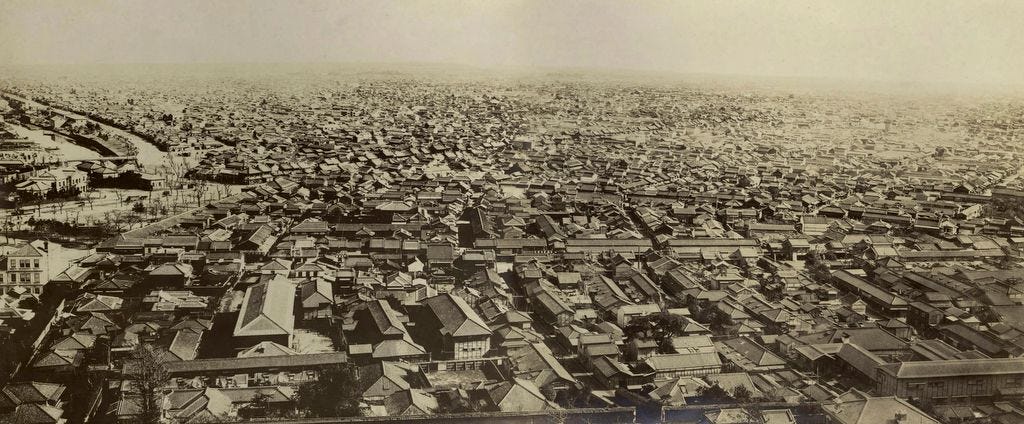

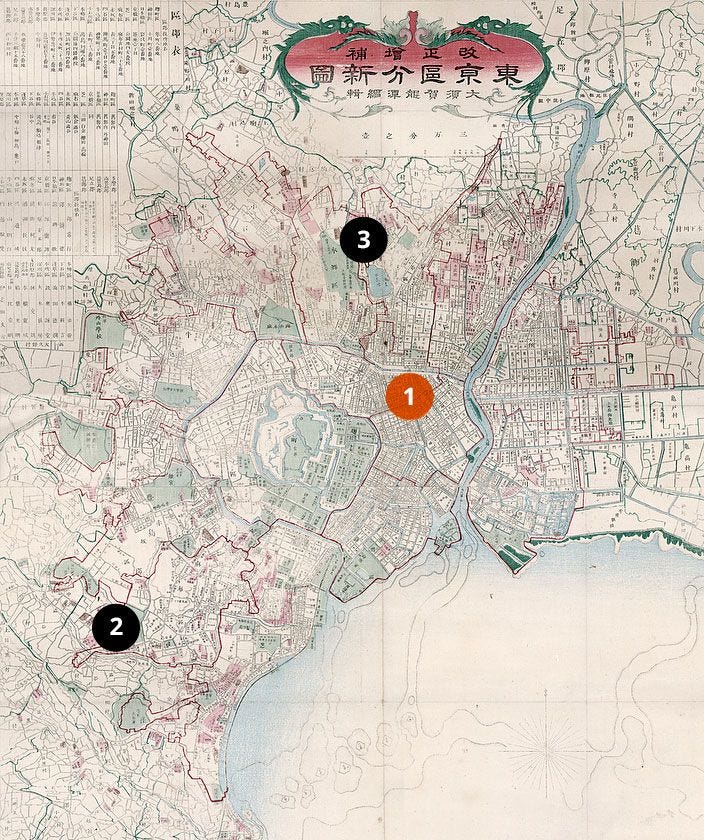

Toshikata grew up in the Higashi Kon'ya-chō sub-district of Kanda, a bustling area in the heart of Edo — the city that would soon be renamed Tokyo. Together with Nihonbashi and Kyobashi, the Kanda area was part of the Shitamachi (or Lower Town) forming the downtown center of Edo. The busy streets were lined with merchants and craftsmen, and the neighborhood where Toshikata lived used to have many dyers, giving the area its name: Kon'ya-chō, meaning “dyer’s shop town.”

As a young boy, he frequently helped out at his father’s workshop. When a friend of his father noticed Toshikata drawing flowers and birds into wet plaster with a trowel, he was impressed by the boy’s artistic ability and encouraged him to pursue painting.

Toshikata’s father hoped he would someday take over the family business. But when his son confessed, “I really want to be an artist,” he let him pursue his passion. When Toshikata turned 14, his father even arranged an apprenticeship with Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, one of the best-regarded ukiyo-e artists of the day.

Training ground

In 1879, Toshikata began his training under Yoshitoshi, moving into his teacher’s house. It was common for Japanese artists to live with their apprentices to facilitate learning through close observation and hands-on learning. His teacher was known by the nickname “Bloody Tsukioka Yoshitoshi” — earned for crafting disturbingly violent, yet very popular, ukiyo-e works. Eimei nijūhasshūku (“Twenty-eight famous murders with verse”) was a particularly gruesome example.

Unfortunately, Yoshitoshi also showed a violent temper in his real life. He was a strict instructor who treated students harshly, both verbally and sometimes physically. Yoshitoshi also began to neglect his pupils. A notorious playboy, he was rumored to spend his days in pleasure quarters instead of properly teaching his students.

The two artists were living in unstable times, as Japanese society was reinventing itself in the wake of the Meiji Restoration of 1868. As this modernization pushed ahead, ukiyo-e went out of fashion, leaving the woodblock industry in dire straits.

Yoshitoshi, who had achieved great popularity and critical acclaim as an ukiyo-e master, was also affected by these difficulties. In 1872, a few years before Toshikata became his student, Yoshitoshi suffered a nervous breakdown. He then developed severe depression, lived in poverty, and stopped all artistic production. He resumed work a year later, and business had recovered by the time he took on Toshikata as his apprentice. However, alternating periods of success and poverty plagued him for the rest of his life. Toshikata’s harsh experience in Yoshitoshi’s workshop may have been rooted in the pressures his teacher faced.

Eventually, the antics of the famed ukiyo-e master proved too much for Toshikata’s father, and the training was cut short. A year into his apprenticeship, his father made him quit and took Toshikata home.

New influences, and a return

And so, Toshikata returned home to work at his father’s workshop. Unfortunately, his father passed away soon after. Then only 16, Toshikata moved in with his stepmother’s relatives, the Ino’okas, who ran a pottery business. There he found the opportunity to sketch decorations for their porcelain products to support himself financially. In another silver lining, he met his first wife, Fusa, the Ino’oka’s youngest daughter.

Still aspiring to become a painter, Toshikata took lessons from two artists of the Nan-ga school, a genre influenced by Chinese litarati painting. He first studied with Shibata Hōshū and later Yamada Ryūtō, who also taught him porcelain painting.

Meanwhile, Toshikata’s former teacher, Yoshitoshi, regained his footing and resumed painting. In the fall of 1882, he exhibited a painting titled Yasumasa Yasusuke-zu at a Meiji government-sponsored art show, receiving critical acclaim. Based on this work, the following year Yoshitoshi created a woodblock triptych, an extraordinary example of ukiyo-e at its finest.

Seeing the masterpieces of his teacher seems to have reminded Toshikata that his heart, too, was in ukiyo-e. He resolved to quit porcelain painting and return to Yoshitoshi to resume his apprenticeship. Initially, the master refused to take him on. But Toshikata showed resolve; no matter how harshly Yoshitoshi rejected him, he refused to give up his efforts. Eventually, Yoshitoshi relented and let him rejoin the school.

Upon Toshikata’s return, Yoshitoshi had only four apprentices left working under him. Apparently, not all of the students could handle the pressure of their eccentric master. This time, however, Toshikata knew what he was signing up for and proceeded to distinguish himself through hard work, quickly gaining Yoshitoshi's trust. The teacher developed a special fondness for the young artist and would later designate him as his successor.

First triumph

When Toshikata turned 19, his teacher gave him the opportunity to make his debut as an artist. Until then, he had done some small works as an assistant; now his master trusted Toshikata to execute a large commission, allowing him to sign it with his own name.

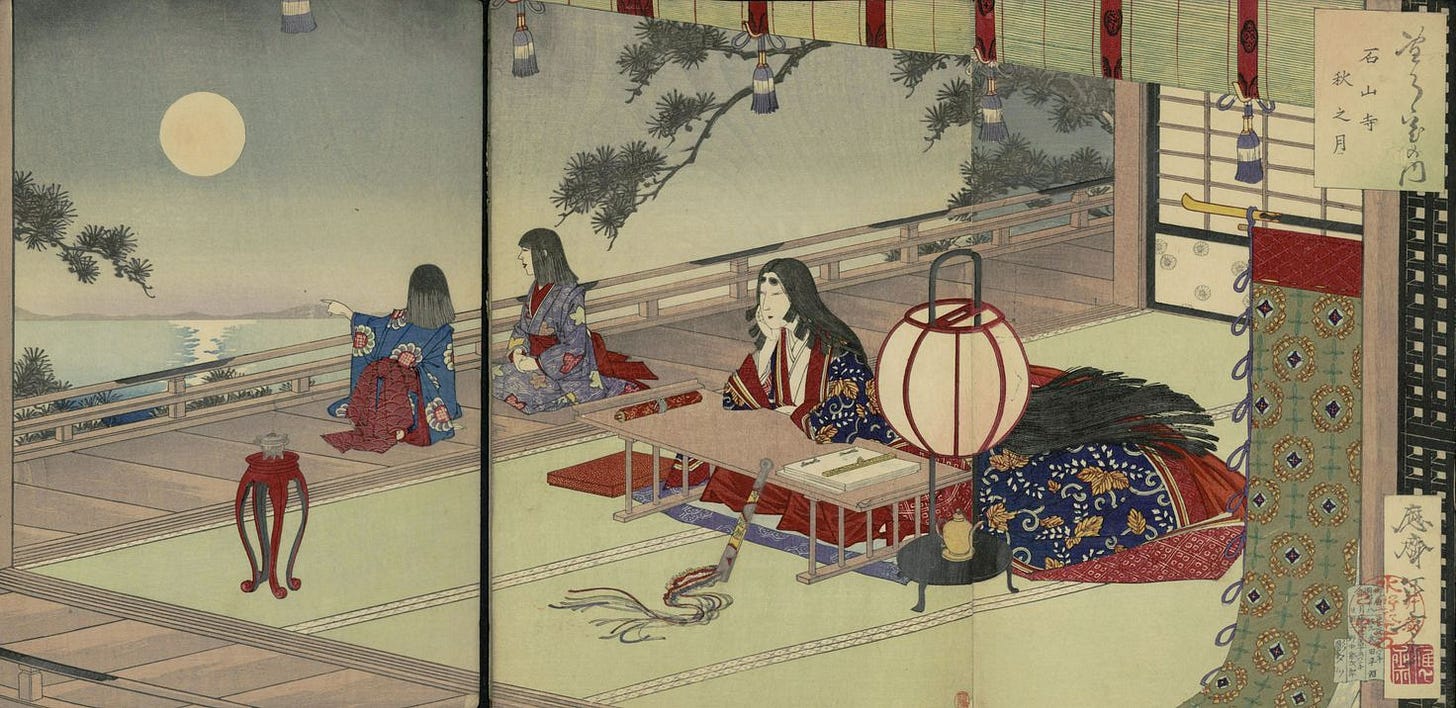

He was to create a multicolored triptych woodblock print depicting a dramatic scene from The Tale of the Heike, an epic account of the power struggle between rival clans for control of medieval Japan.

Toshikata rose to the occasion with the spectacular debut, Sasaki Moritsuna Bizen no kuni Fujito no watari ni Heigun o osowanto gyojin ni mizu no senshin o tou zu (“Sasaki Moritsuna Asking Fisherman to Reveal the Shallows Where His Troops can Cross and Attack the Taira Forces at Fujito in Bizen Province”). Toshikata had emerged from the shadow of his master. Published in 1884, this was probably the first nishiki-e to bear the signature, “Mizuno Toshikata.”

Following his debut work, Toshikata created a series of three nishiki-e woodblock prints titled Setsu-getsu-ka (“Snow, Moon, and Flowers”), which depicted scenes based on The Tale of the Heike, set in the late 12th century. Toshikata developed a special interest in historical subjects and would later create many works featuring such themes.

This was the first part of the eight-part newsletter series on the life and work of Mizuno Toshikata.

In the next newsletter, Part 2: Finding his niche, I would like to look at his early book and newspaper illustrations.

Thank you for reading The Arts of Japan’s Substack newsletter.

I hope you enjoyed it! If you did, please take a moment to hit the heart button at the top of the email or in the Substack app.

Feel free to leave a comment! I would love to hear your thoughts. If you have additional information on the subject or found an error, your constructive feedback is always welcome too.

And, of course, feel free to share the post or subscribe to The Arts of Japan if you haven’t yet done so:

The Arts of Japan is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Stefan Yanku adapted this Substack issue from an article he published on The Arts of Japan’s website. For further credits and references, please visit the original article at https://artsofjapan.com/en/profiles/mizuno-toshikata

For copyrights and usage permissions, please refer to the article linked above and the general statement on our website, available at https://artsofjapan.com/en/impressum.

Very interesting and I bet that must have taken time to research and write. Good work! Nice to see your collaboration with Kjeld Duits, whose research I also admire!

Absolutely fascinating, I loved reading this and look forward to reading more. Thank you.