Hashiguchi Goyō – The Printmaker

The third and last issue of a three-part series on the life and work of Hashiguchi Goyō, a Japanese painter, book designer and printmaker active in the early 20th century.

In the previous two issues we looked at the early life of Hashiguchi Goyō, his career as a book designer and his paintings.

As mentioned in the first issue, Goyō suffered from health issues, and during the summer of 1910, Goyō traveled to Beppu in Oita Prefecture — a region famous for its spas — to recover.

Now in his thirties, Goyō sought to distance himself from oil painting as he searched for a new medium to ignite his creativity. Inspired by his visits to hot springs and the beautiful landscapes, he found themes for a new creative direction that was finally coming to life. Perhaps feeling liberated by the prize money he received for his Mitsukoshi poster, he turned his attention to woodblock printing.

Goyō went on to a period of extensive research into the techniques of Ukiyo-e printing and started to publish many articles on the subject, mainly on the classic works of Utagawa Hiroshige and Kitagawa Utamaro.

Along with his research, Goyō painted watercolor studies inspired by his travels in Oita and began experimenting with creating his own woodblock prints.

In 1913, the watercolor painting Onsen, depicting a scene at a hot spring, was exhibited at the National Art Association’s 1st Western Art Exhibition. In the subsequent two years, he completed two woodblock prints, both published as frontispieces of the literary magazine Shin Shōsetsu (New Novel).

In response to these activities, he was approached by the publisher Watanabe Shōzaburō in 1915, who was looking to commission a suitable artist for his woodblock printing project that would later evolve into the Shin-hanga movement. Watanabe was looking to “revive” the art of woodblock printing with a modern approach and contemporary artists.

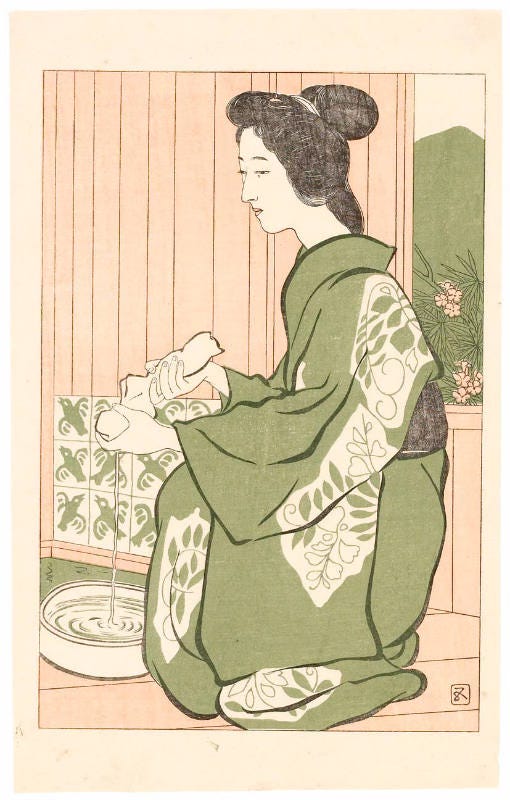

Goyō was persuaded and designed the print Yokujō no on'na (Woman After the Bath). The print was executed in the traditional cooperative system, where at least three expert artisans — a designer, carver and printer — collaborate under a publisher’s direction. After a series of experiments at Watanabe’s workshop, the work was released the following year as a limited edition of 100 prints. Today, Yokujō no on'na is now acknowledged as the first Shin-hanga print.

However, Goyō appeared to be dissatisfied both with the result and with his collaboration with Watanabe. Watanabe wanted to continue the partnership, but Goyō chose to take a step back to improve his skills and reassess his approach to woodblock prints.

He embarked on another period of careful research into the techniques of Ukiyo-e printing. Between 1917 and 1919, Goyō supervised three series of print reproductions of early Ukiyo-e masters — over 300 individual woodblock reproductions in total, published together with essays and commentaries that he penned.

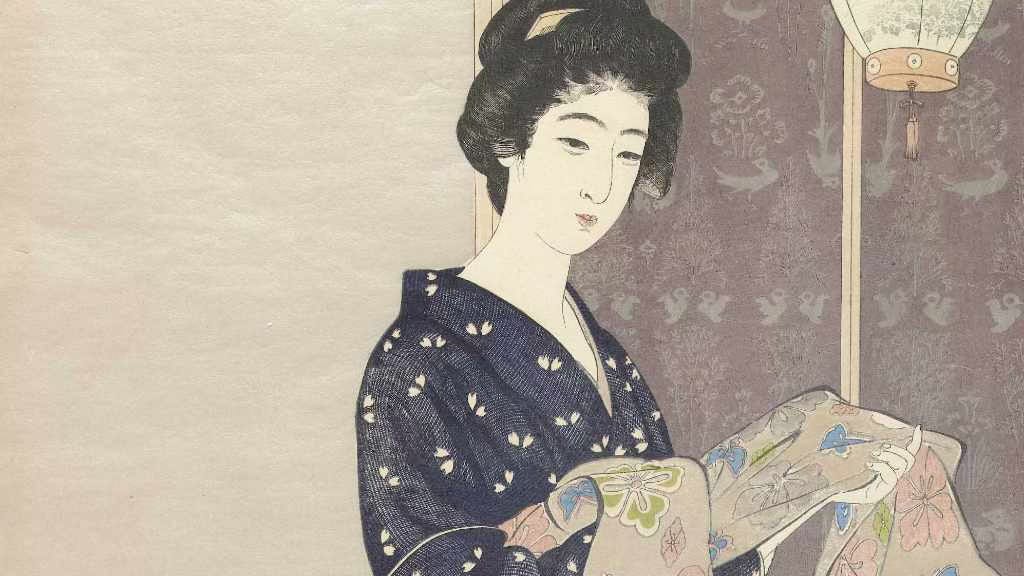

In March 1918, two years after he collaborated with Watanabe and a period of creating sketches and studies, Goyō self-published his first woodblock prints, including Yabakei (Yaba Gorge) and Keshō no on’na (Woman Applying Makeup).

He continued to be very prolific over the following two years. By 1920, he had remarkably self-published ten prints, including the work he is probably best known for, Kami sukeru on'na (Woman Combing Her Hair).

The accumulated fatigue from this production proved to be fatal. By the late 1920s, Goyō’s health was in rapid decline. He supervised his last print, Onsen Yado (Hot Spring Inn) from his hospital bed, and died on February 24, 1921, at the age of 41.

Goyō left behind several unfinished print designs upon his early death. His elder brother and nephew later commissioned the production of a selection of prints based on the works.

Goyō’s impressive legacy ranges widely from painting and book design to writing about Ukiyo-e and publishing reproductions of early woodblock print masters. He managed to blend traditional and modern techniques with Japanese and Western aesthetics into his own vision. He eventually played a key role in revitalizing the woodblock print medium through his works, which have established his reputation as one of the greatest of the Shin-hanga artists.

Next issue:

After taking a break next week, we'll look at the life and work of Hyakutake Kaneyuki, a diplomat of the fledgeling Meiji government who became the first Japanese artist to paint a nude in oils.

Previous issues:

Stefan Yanku adapted this Substack issue from an article he published on The Arts of Japan’s website. For further credits and references, please visit the original article at https://artsofjapan.com/en/profiles/hashiguchi-goyo

For copyrights and usage permissions, please refer to the statement on our website, available at https://artsofjapan.com/en/impressum.

I really enjoyed this, thank you.

Another great article, Stefan. I was not aware that Yokujō no onna was considered to be the first Shin-hanga print. It is beautiful, yet Hashiguchi's later prints are so much better.